Fashion is usually framed as self-expression, yet a new exhibition in New York reveals just how tightly it’s woven with psychology. Dress, Dreams and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis, now on view at The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, traces the way clothing reflects desire, identity, and the unconscious.

With nearly 100 curated pieces from leading designers, the exhibition sheds light on the hidden meanings behind garments, proving that fashion is far more than fabric and design.

Fashion as a Mirror of the Mind

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, may be remembered for his theories, but he also had a sharp sense of style. Always dressed in perfectly tailored English suits, Freud understood that clothing communicates power and identity. His ideas about dreams, desire, and symbols remain relevant in interpreting how fashion operates on both personal and cultural levels.

The exhibition builds on this connection, presenting designs that reflect psychological concepts. From structured bustiers to velvet jackets embroidered with mirror-like illusions, each piece speaks to the way clothing reflects inner emotions and hidden drives.

The Language of Fashion and Psychoanalysis

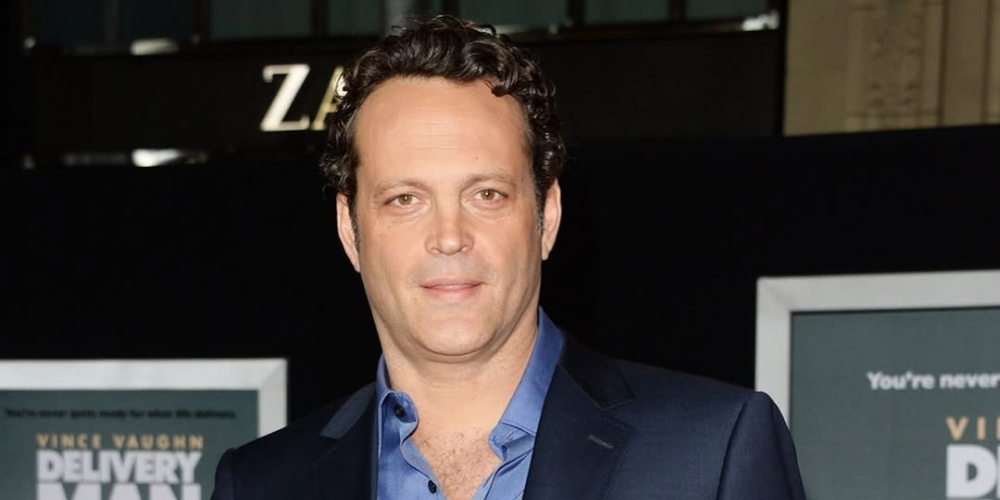

sidewalkhustle.com | In the 2012 short film "A Therapy," Prada uses a psychoanalyst trying on a patient’s coat to question fashion.

Fashion has long been tied to psychoanalytic thought. Designers have drawn direct inspiration from Freud and his theories:

Marc Jacobs released the “Freudian Slip” in 1990, a dress that wittily played on Freud’s most famous phrase.

John Galliano created the Dior collection “Freud or Fetish” in 2000, blending fantasy with psychological symbolism.

In 2012, Prada presented A Therapy, a short film where a psychoanalyst tries on his patient’s coat, questioning the meaning of fashion itself.

These examples reveal how designers treat clothing as more than adornment—using it as a tool to explore desire, sexuality, and the subconscious.

Symbols, Desire, and Power in Clothing

Fashion has long carried symbolic meaning. Freud pointed to the role of phallic symbols, and the exhibition showcases bold examples. Top hats, stilettos, and Jean Paul Gaultier’s cone-bra dress, made famous by Madonna, stand out. These pieces show how clothing can project sexuality and power, while also fueling cultural debate.

The exhibition also explores the idea of the “phallic woman” and the way clothing reshapes femininity. A red leather bustier by Issey Miyake suggests both strength and sensuality. Meanwhile, Rei Kawakubo’s architectural designs turn the body into a sculptural form.

Together, these works show how fashion acts as both armor and art, while also challenging traditional views of the body.

Shifting Erogenous Zones in Fashion

Fashion often highlights certain parts of the body. Psychoanalysis helps explain why this happens. Evening gowns once drew focus to arms and décolletage. In the 1920s, shorter hemlines put legs on display. By the 1930s, open backs added a new element of allure. Fashion history shows how these choices reflect cultural rules and desires.

Some historians claimed that erogenous zones shift to suit the male gaze. Curators argue instead that outside forces shaped these trends. One example is the Hays Code, which limited sexual imagery on screen between the 1930s and 1960s. What could not be shown openly gained intrigue. A glimpse of the back, once modest, started to feel sensual.

Clothing as Armor, Hug, and Statement

Instagram | museumatfit | The exhibit reveals that fashion is a cultural expression, not just clothing.

Fashion is often described as a second skin, but it functions in many ways beyond appearance. Clothing can:

1. Offer protection, like armor against the outside world.

2. Provide comfort, wrapping the body in fabrics that feel like a hug.

3. Highlight sexuality, framing or emphasizing specific physical features.

The exhibition brings these ideas to life through pieces such as Schiaparelli’s 1938 “Hall of Mirrors” jacket and Jennifer Lopez’s famous green Versace dress, which sparked a wave of daring “naked dresses” on red carpets.

Why Fashion and Psychology Intersect

At its core, fashion reflects the paradox of visibility: the wish to be noticed and the fear of being too exposed. Pascale Navarri, the French psychoanalyst, argues that clothes live in this delicate balance between presence and concealment. Whether a designer gown or an ordinary T-shirt, every garment carries signals of both self and society.

The New York exhibition underscores this point: fashion is never just surface. It channels psychology, history, and symbolism all at once. From Freud’s austere suits to radical runway creations, clothing reveals more than it conceals.

Fashion, in this sense, becomes a language of desire and identity—a reminder that every garment hides layers of the human story.